“The Moment in Time in the History of Black Theatre”

by Dr. Quincy Thomas, Assistant Professor of Theatre (editorial support from Dr. Regina Stevens-Truss, Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry)

The Nation celebrates Black History this month and every February – “Happy Black History Month” to all. Every February, for 28 to 29 days on a good year, the many contributions of Black Americans is highlighted and featured in many settings – so glad that at K we do this every month.

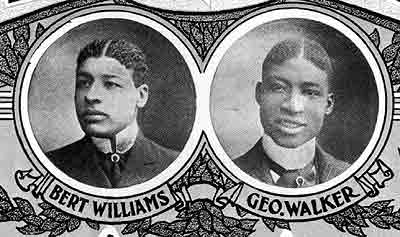

“Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar and Grill” (2014); “Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk” (1996); “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” (1984); “The Wiz” (1975); these are but a few of the offerings by Black theatre practitioners that, to this day, stand as a testament to artistic excellence within musical theatre’s historical canon. All of these stories speak to the eternal struggles that are all too well known within the Black community. They possess themes and messages that for far too long have resonated throughout the diaspora. But while today, in 2023, many appreciate current day Black art and performance, we would be remiss if we did not take time to track the harrowing paving of a path that has allowed shows such as Hamilton (2015) to even be seen beneath the garish lights of Broadway – this is the story of George Walker and Bert Williams.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Broadway was for many, as it is today, synonymous with quality and commercialism. Black theatre practitioner longed to have their faces caressed by the spotlight of a Broadway stage, as so many practitioners still do, whether they want to admit it or not. For Black theatre practitioners however, entry into this homogenized “Mecca” was nigh impossible, even in the minstrel era.

Minstrel shows were a wildly popular form of American entertainment that were built upon themes of racial stereotype that have endured to this day. In order to tell these stories of ignorant, lazy, and clumsy people of African descent, White actors would blacken their faces with makeup and perform in a show that moved through a three-part structure, beginning with jokes and songs, transitioning to comical skits and monologues, and ending with political critique and parodies of classical literary pieces or current events. This uniquely American form of theatre brought unfavorable representations of Blackness to Broadway’s stages.

The popularity and longevity of the minstrel show was a rallying cry for many Black American nineteenth and twentieth century artists who sought to upturn Broadway’s racist constructions of Blackness. There are, of course, the names that we know—the Harlem Renaissance magic of the poet Langston Hughes (1902-67), and the timeless power of playwright Lorraine Hansberry (1930-65). But few know of George Walker (1873-1911) and Bert Williams (1874-1922), two performers to whom Black actors, such as myself, owe an unpayable debt.

George Walker grew up in Kansas, watching his family perform in minstrel shows, thus exposing him to the popular entertainment at an early age. As he grew older, Walker moved all about the U.S., utilizing his skills in acting, comedic facial contortions, singing, and playing both instruments and dried animal bones. These talents, standards in the minstrel performer’s toolbelt, he put to use on the back of wagons owned by snake-oil salesmen and charlatans, as well as in minstrel shows.

The Nassau, Bahamas born Bert Williams spent his early years migrating with his Danish father and his mother, who was of Spanish and African ancestry. By the time Williams and his family landed in California, his dream was to be an engineering student at Stanford University, but financial woes forced him to seek out more immediate ways to make money. He started a small touring minstrel company, in which he was the only Black man, and as such, he traveled the West Coast. Williams, a fast-footed physical comedian, did not find success with his own troupe and, in 1893, he found himself in San Francisco, where he met George Walker.

Together the duo crafted fast-moving song and dance numbers and crowd-pleasing comedic skits. They performed from Los Angeles to Denver and eventually in New York City. When they weren’t working, they would go to minstrel shows with White casts and observed the banal and uneducated portrayals of Blackness. In the essay, Early Black Americans on Broadway, Monica White Ndounou gives readers a glimpse into Walker’s plan to address the reappropriation of Black representation on vaudevillian stages:

“We thought there seemed to be a great demand for Black faces on the stage, we would do all we could to get what we felt belonged to us to us by the laws of nature. We finally decided that as when men with Black faces were billing themselves as ‘coons,’ Williams and Walker would do well to bill themselves the Two Real Coons.”

White men in blackface could not capture authentic Blackness in the ways that two men of African descent could, but this meant that Williams and Walker were forced to prop up the same damning stereotypes that they themselves were fighting to overturn. As they fought to carve out a place dedicated to Black comedy in Eurocentric spaces, both Williams and Walker were forced to deal with the racial terrorism brought on by white audience members and white performers, terrorism that often turned violent. Despite this, both men continued to do the life-threatening work and, in 1896, they were cast in The Gold Bug, making them the first Black Americans on Broadway. While leading the way for Black performers in the late nineteenth century, Williams and Walker produced seven original works that spoke to issues of African language, political satire, and colonization, and they told these stories through the usage of comic opera, the infusion of African themes into American performance tropes, and musical theatre.

The legacy of these two men, the safety that they sacrificed and the emotional and mental weight that they carried in order to do what they loved to do, lies before Black actors today. The history of Black Theatre is one of a roughly hewn path, strewn with blood, tears, joys, and excellence of many beautiful men and women on whose backs many profited from hatred.

This is something that I think about every time I’m allowed to interact with and on the stage, and it is something for which I am eternally thankful – as should we all be.

Additional Information

Additional information about Williams & Walker can be found at:

- Wikipedia article, William and Walker Co.

- Wikipedia article, George Walker (vaudeville)

- Wikipedia article, Bert Williams

Questions?

Questions regarding this story – contact Dr. Quincy Thomas (Quincy.Thomas@kzoo.edu); for questions about the 19 stories, especially if interested in submitting a story – contact Dr. Regina Stevens-Truss (Regina.Stevens-Truss@kzoo.edu)