Medical Injustices in the History of Black Americans

Written by Dr. Fari Nzinga and Dr. Regina Stevens-Truss

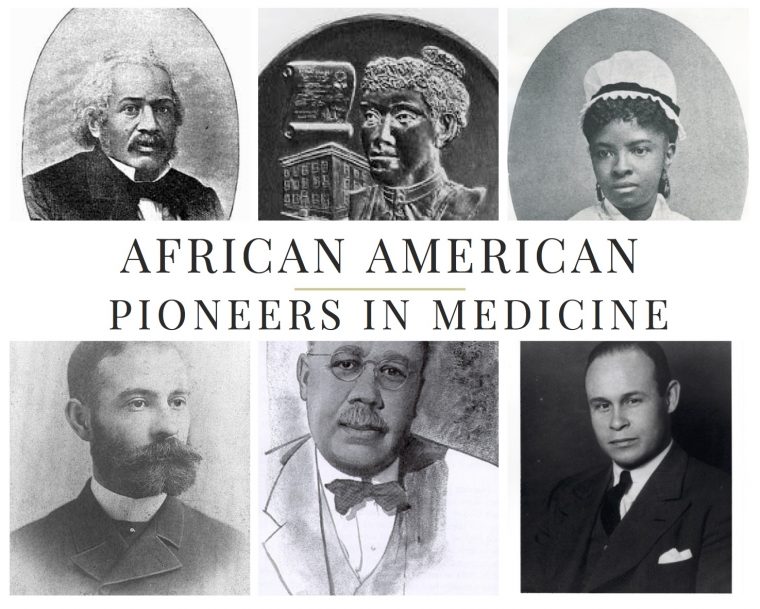

Happy Black History Month has been said in the USA since 1970. During the month of February, we celebrate the achievements of Black people and honor historical pioneers. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, several institutions have honored Black Pioneers in Medicine during February Black History Month Celebrations (see these Black medical pioneers). In 2022 Kalamazoo College has joined in these celebrations (ARRK event on Feb 15, Henrietta Lacks event on Feb 17, and this Feb 19 Black History story).

Throughout American history however, “Black people have endured a medical system that has been simultaneously exploitative and dismissive. And the damaging implicit and explicit biases present in our medical system do not suddenly vanish because we are in the middle of a pandemic. In fact, the pandemic has made them impossible to ignore” (referenced from Vox article, how medical bias against black people is shaping Covid-19 treatment and care).

To understand why it is that during a global pandemic so many Black Americans are distrustful of the medical authorities and are hesitant to get vaccinated, one needs to look back at history.

The next two stories adapted from the Annals of American Medical History are but two examples of medical malpractice towards Black people that may help shed light on some of the roots of a bigger problem.

Many of us may have heard of the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male (discussed later in this piece) but we may not have heard the story of Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy before.

1840s – Montgomery, Alabama

Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy, considered the Mothers of Modern Gynecology according to Women & the American Story, were three enslaved women who lived and worked on different plantations near Montgomery, Alabama, in the 1840s (referenced from Life Story: Anarcha, Betsy and Lucy-The Mothers of Modern Gynecology). After giving birth, these three women developed a painful medical condition that caused them to lose control of their bladders and bowels. At that time, enslaved women with this condition were separated from other slave workers as there was no treatment for the condition. These women’s frustrated slave owners wanted a cure, so that the women would be able to resume their hard labor to earn them money. Dr. J. Marion Sims caught the interest of these women’s slave owners, as he and others in the 1800s were very interested in medical advancement and experimentation. Dr. Sims, while attempting to treat and cure Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy, leased them for the duration of their treatment, ensuring his complete control over their bodies. Between medical procedures and experiments, the women worked for the Sims family, and for 5 years, Dr. Sims would operate on Anarcha, Betsy, Lucy and other women in rooms crowded with doctors who had traveled for miles to observe the details of his procedures. These women were naked and in chains while on the operating table. Dr. Sims did not use anesthesia in his many procedures, partly because doctors feared the potentially fatal side-effects of anesthesia, and partly because it was commonly believed that Black women did not experience pain the same way white women did (this belief, BTW, still makes its way into medical practices today). Many of his medical experiments ended up being failures, causing his white male assistants to quit. Undeterred, Dr. Sims trained Anarcha, Betsy, Lucy to be his assistants. In time, they became skilled medical practitioners in their own right, caring for each other and others during their recoveries. Finally, after enduring over 30 painful and humiliating surgeries, Anarcha, Betsy and Lucy were returned to their enslavers to continue to toil on their plantations. The exploitation of Black women did not end with the Civil War, nor with emancipation. With the lens of 2022, one could imagine that this story could only happen during slavery…

Almost 100 years later, 1930s – Tuskegee, Alabama

In 1932 at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Black men in Macon County were targeted for research. The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” (now referred to as the “USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee”) was a study conducted for a little over 40 years (1932-1972) by the United States Public Health Service (see Racism and Research: The Case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the Ted Talk, Ugly History: The U.S. Syphilis Experiment by Susan M. Reverby). The study initially involved 600 Black men – 399 who had syphilis and 201 who did not have the disease. Researchers told the men that they were being treated for “bad blood,” a local term used to describe several ailments, including syphilis, anemia, and fatigue. During their “treatment” and “free medical exams” sessions the men were provided free meals as an incentive, but they were subjected to painful procedures. Researchers wanted to understand the course of the disease (which ends in death and causes severe organ damage along the way), as well as whether the disease manifested differently in Blacks and Whites. During the course of the 40 years, many of the 600 subjects died and they were provided and promised burial insurance. Although treatment was the promise, the reality was that the men received no treatment at all. And even after penicillin was discovered as a safe and reliable cure for syphilis in 1943, the majority of the Tuskegee patients did not receive it – in fact, they were banned from receiving this treatment as a way to continue the study.

On July 25, 1972, Associated Press reporter Jean Heller broke news about the study (see article, Black men untreated in Tuskegee Syphilis Study) that severely damaged public trust in the American medical establishment. As a result, the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs appointed an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel to review the study. The advisory panel concluded that the study was “ethically unjustified and advised stopping the study.” A month later, the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs announced the end of the study (see the Memorandum Terminating the Tuskegee Syphilis Study). The following year, in March 1973, the panel also advised the Secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) (now known as the Department of Health and Human Services) to instruct the USPHS to provide all necessary medical care for the survivors of the study. The Tuskegee Health Benefit Program (THBP) was established to provide these services. At the same time, a class-action lawsuit was filed on behalf of the study participants and their families, resulting in a $10 million, out-of-court settlement in 1974. In 1975, participants’ wives, widows and children were added to the program. In 1995, the program was expanded to include health, as well as medical, benefits. The last study participant died in January 2004. The last widow receiving THBP benefits died in January 2009. Participants’ children (10 as of 2021) continue to receive medical and health benefits and continue to fight for justice.

Almost 90 years after the start of the Tuskegee Study and 49 years (1973) after these men and their families were provided medical benefits, many Black Americans have poorer health outcomes than their White counterparts in part due to racist thinking and policies that prevail in our society. Despite major advances in obstetrics and gynecology, Black women still suffer higher rates of maternal mortality in the United States. Black patients continue to receive less pain medication for a myriad of conditions including broken bones and cancer, and Black children receive less pain medication than white children for conditions such as appendicitis – still today, some medical practitioners inaccurately believe that Black people experience less pain than other human beings. It’s no wonder that Black people distrust “science” and the medical establishment!

Honoring Black Medical Pioneers

Let’s continue to honor medical pioneers, but most importantly

let us work on equalizing how every member of society is treated.

Medical Pioneers to Celebrate

- Black History Month honors medical pioneers for 2022 by Fox29 Philadelphia

- Medical Pioneers to Celebrate this Black History Month by Senior Helpers

- 25 Medical Pioneers to Celebrate this Black History Month by Becker’s Hospital Review

- Black History Month 2021 – Celebrating Health Pioneers & Today’s Leaders by the New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM)

- Celebrating Black Health and Wellness by Sparrow

Continue to Celebrate Black History Month…

Check out these further readings:

- Goldenberg, Maya J. Vaccine Hesitancy: Public Trust, Expertise, and the War on Science. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1ghv4s4.

- HOBERMAN, JOHN. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism. 1st ed., University of California Press, 2012, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pq0j8.

- HOBERMAN, JOHN. “Why Bioethics Has a Race Problem.” The Hastings Center Report, vol. 46, no. 2, [The Hastings Center, Wiley], 2016, pp. 12–18, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44159426.

- OWENS, DEIRDRE COOPER. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. University of Georgia Press, 2017, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1pwt69x.

- Sirleaf, Matiangai. “DISPOSABLE LIVES: COVID-19, VACCINES, AND THE UPRISING.” Columbia Law Review, vol. 121, no. 5, Columbia Law Review Association, Inc., 2021, pp. 71–94, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27033038.

Would you like to contribute a story?

Anyone can contribute a 19 story. Contact Regina Stevens-Truss at Regina.Stevens-Rruss@kzoo.edu for information on how to get started!